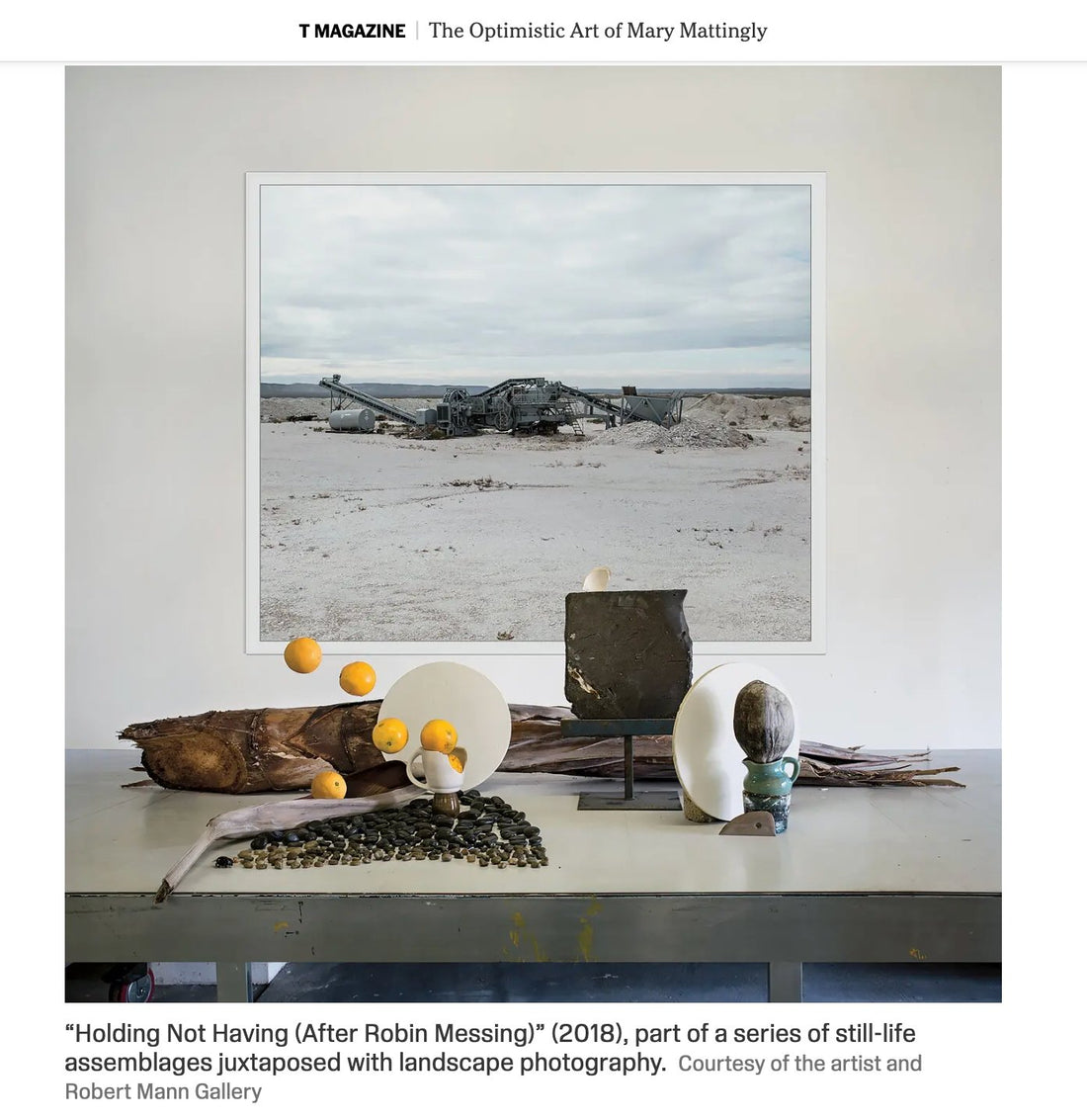

The Optimistic Art of Mary Mattingly

The artist’s work addresses future climate crises while attempting to make the urban environment a better place to live right now through art. More about Mary Mattingly's art about the climate crisis.

Sept. 30, 2022

IN THE SUMMER of 2009, the artist Mary Mattingly moved out of her New York apartment and onto a barge for a five-month experiment in off-grid urban living. With salvaged-wood cabins; a geodesic dome; a garden sprouting lettuce, squash, berries and corn; a rainwater filtration system; and solar panels that (at least on sunny days) produced enough power for brief hot showers, “Waterpod” was both a floating sculpture and a mostly self-sufficient community. Mattingly, who celebrated her 31st birthday onboard, rarely stepped ashore. She shared the space with four chickens and a rotating cast of friends, who also lived aboard the vessel. The 100-foot-long, 30-foot-wide barge floated around the New York waterways, docking for two-week stints at public piers across the five boroughs. A tugboat brought it from place to place, but the rest of the power aboard the craft came from the sun and a jury-rigged stationary bike.

Mattingly had spent three years raising funds and petitioning city, state and federal agencies for permits to make the commune possible, inspired by a vision of mobile life in a waterlogged world. The city is vulnerable to rising sea levels, and the government, she felt, was doing little to fortify its fragile infrastructure. With “Waterpod,” Mattingly wanted to practice the nomadism, resiliency and collective resourcefulness that climate change might increasingly demand. Three years later, Hurricane Sandy flooded nearly a fifth of New York City, demonstrating how utterly unprepared the metropolis was for the megastorms scientists predict will only become more common.

Throughout her career Mattingly has created prescient environmental projects that address current crises and potential cataclysms: What might the good life look like if cities that depend on precarious supply chains became more self-reliant? How could public parks help relieve urban hunger? Her work has been called apocalyptic, and yet the label seems like lazy shorthand for her attempts to grapple with potential calamities. Her public projects reflect a broader movement of city dwellers interested in reclaiming underused outdoor sites and forging more intimate connections with local ecologies. “Right now, people are looking at landscapes to see who they’re serving and not serving, and why,” said Lindsay Campbell, a research social scientist with the U.S.D.A. Forest Service who has collaborated with Mattingly. The artist, she said, reinvents the possibilities of urban life “to imagine other worlds and other ways of being.”

Mattingly, 44, brings a wry sense of humor to this lineage, which is part of what makes her work relatable. “People feel this every day in bureaucratic social systems,” she said. “There are just layers upon layers upon layers of absurdity that it takes to go through a day in a litigious place — that’s part of what inspires me to make new work. Feeling caught in that absurdity loop and then trying to respond to it.”